Every day, billions of telephone users take advantage of an early 1980s technology to help them decide if they want to answer an incoming call. I was fascinated by the technology and wanted to learn about its origins.

The December ’17 Lab Day was spent in pleasant research digging into the development of Method and apparatus for displaying at a selected station special service information during a silent interval between ringing (U.S. patent 4582956, April 15, 1986) a technology also known as “Caller ID”.

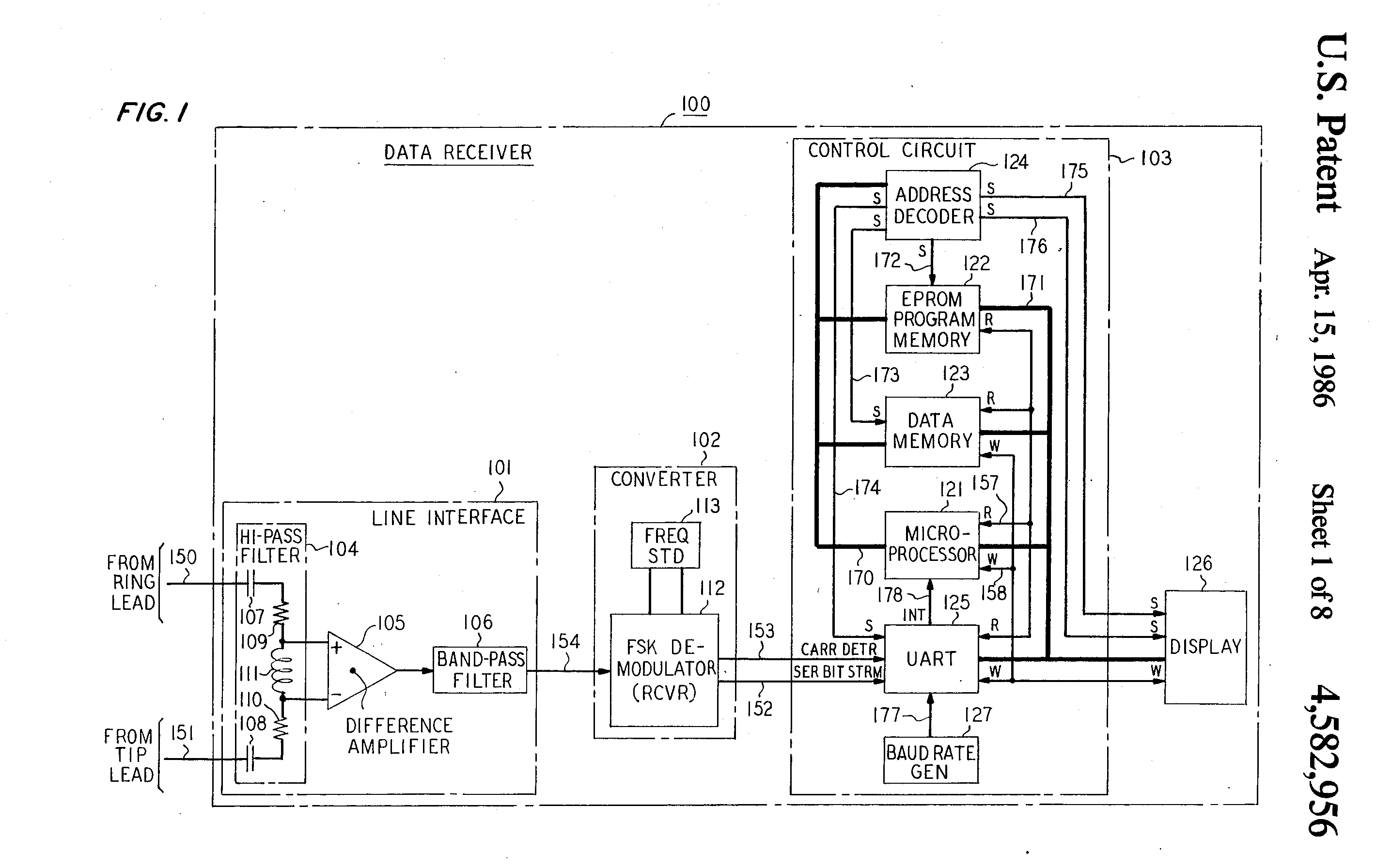

Figure 1 from the U.S. Patent filing showing how to transmit Caller ID data TO the phone receiving the call.

Figure 2. A block diagram of the Caller ID receiver and data processing, as seen by the receiving telephone.

The Problem

Modern Caller ID was developed by AT&T Bell Labs engineer Carolyn A. Doughty. Her U.S. Patent narrative points out that while other means already existed to glean a caller’s phone number, these methods were either functional after answering the phone (such as a telephone office system that announced the phone number verbally), or required an additional communications link to the Central Office to pass the caller data to the called “station”.

These methods were labelled “annoying” and “inefficient” in the patent filing.

Imagine if this technology hasn’t been advanced to modernity: One would receive a phone call and upon answering an automated voice at the Central Office would tell you who is calling (presumably the calling party could hear your anguished reaction to the time wasted listening to the automated voice).

The Central Office End

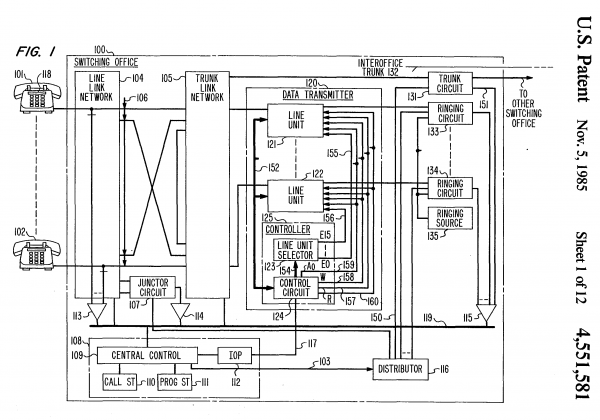

To modernize this technology and lay the ground work for future calling features, Carolyn Doughty also developed the “back end” technology for transmitting the caller data from the telephone central office to the receiver in a separate U.S. Patent 4551581 titled Method and apparatus for sending a data message to a selected station during a silent interval between ringing.

The method used is elegant and straightforward, as shown in Figures 1 above.

When one places a telephone call there is a two second “ring” followed by four seconds of silence, then another two second “ring” then silence—a familiar pattern that continues until the caller hangs up or the call is answered.

In the four seconds of silence between the first and second ring, a frequency shift keyed (FSK) signal is created using 2025Hz (logic “0”) and 2225 Hz (logic “1”) and transmitted to the receiving telephone. You may recognize FSK signaling; it’s similar to that used by telephone data modems in the late, great dial-up Internet days.

The receiving telephone equipment, as shown in Figure 2, contains an FSK demodulator that in turn feeds a UART and microprocessor that converts the demodulated signal into recognizable serial data. The data structure contains the following fields: Message type; character type; the data itself; and a checksum. The resulting data can be sent to a display and/or stored in processor memory for later recall.

In landline to mobile phone calls, it appears that the first ring is delayed to the mobile phone until the Caller ID data is ready for simultaneous delivery to the consumer. This is a convenience feature that allows mobile customers to see who is calling as their phone begins to ring.

DIY…Not So Much

When I tried browsing electronics supply houses’ catalog for chips and chipsets that process Caller ID data—as for DIY projects—I found few chips and many obsolete chipsets; in this day and age of mobile devices, discrete electronic components for landline telephones seem to be getting rarer. An Amazon product search for “Caller ID” returned a number of inexpensive products that make a DIY “Caller ID” project not practicable; it’s cheaper to buy an off the shelf product than to DIY.